Voyaging through the unruly swell, storm and pirates in the Indian Ocean, children were originally sexually exploited in the Philippines after being shipped to the country as slaves from Africa in the 16th century.

Five hundred years later to today, Filipino children can be ordered online for sexual services. And If they’re not being abused, some children – as young as 15 – are now becoming pimps.

Barnett, a Destiny Rescue rescue agent in the Philippines funded by Child Rescue, says the face of human trafficking is continuously changing but remains “as rife as ever” in the country.

It is forever evolving into a darker trade,” the rescue agent says.

Snapshot of the crisis

Located as an archipelago in Southeast Asia, the Philippines is home to more than 108 million people across its 7000 islands. Human trafficking curses the country partly because it is riddled with poverty.

About 18 million lived below the poverty line in 2018, according to anti-poverty financial institution Asian Development Bank. Many poor people are farmers in rural areas, but a portion lives in slums in the cities, like the capital, Manilla.

Between 60,000 to 100,000 children, typically poor girls aged 14 to 17, are trafficked each year through migration or within the country, according to a report in 2016 by global anti-child exploitation network ECPAT International.

The Philippines has become a poster child for human trafficking globally, but how did the crisis sprout, grow and become a towering issue in the country?

How it all began

In the 16th century, Spain colonised the Philippines after a Spanish explorer discovered the island nation, resting his galleon’s bilge on its shore.

Global slave trading was trending at this point in history – a phenomenon leading to one of the earliest records of trafficking in the Philippines.

Called the Indian Ocean Slave Trade, a portion of between 10 to 11 million Africans were shipped to Southeast Asia between 650 to 1900, according to a report last year by online research institution International Institute for Asian Studies.

Tens of thousands of slaves were potentially dumped into the Philippines.

While many slaves worked as maids or farmers, female slaves in Manilla were also vulnerable to “sexual expectations” by their masters in the 17th century, an article said in 2019 by online news publication The Conversation.

The Spaniards, who controlled the country and were Roman Catholic, viewed sexual abuse of slaves as a sin and outlawed the importation of female slaves, yet “the practice continued,” the article added.

After this early stage of human trafficking in the nation, the crisis started branching into two primary categories: migration and domestic.

The Philippines’s tourism industry supports the latter.

Tourism begins in the 1880s

Tourism is a big factor in creating demand for commercial child sex exploitation within the Philippines, which is a “major” concern, according to a report in 2016 by global anti-child exploitation network ECPAT International.

Tourism in the nation first looked like businessmen and sailors arriving to trade after the Spaniards built railroads, electricity and telegram in the late 19th century. Soon one of the first hotels, The Manilla Hotel, was created.

By the 1940s, the country’s first airport and airline were born, alongside more hotels and resorts, which helped attract about 50,000 visitors in 1960. The number of visitors each year has soared since then, reaching over eight million in 2019.

The Philippines – with its tourism slogan, “It’s more fun in the Philippines” – is today a tourist hotspot.

The country has a gift for any visitor, flaunting pristine beaches, rich cuisines, colourful festivals and the Chocolate Hills, a region featuring more than 1000 dome-shaped hills that turn brown in summer.

The Chocolate Hills comprises 1200 to 1700 hills, standing up to 50 metres tall.

But some tourists – young, old, married or single – frequent the red-light districts in urban areas in the Philippines. In pubs, karaoke bars and nightclubs in these areas, traffickers sell girls and women to customers for sexual services.

Traffickers, who range from syndicates to relatives, typically recruit impoverished girls and women from villages in rural areas after baiting them with the false promise of a job or education.

Once a trafficker hooks them, girls and women can be “locked up, drugged, forced to provide sexual services and heavily guarded,” according to a report in 2018 by Thailand-based education and research agency UNESCO Bangkok.

Migration kicked off in the 1960s

On top of domestic trafficking, Filipinos can be exploited overseas.

Migration is a “deeply rooted” culture in the Philippines, according to United States-based think tank Migration Policy Institute. Most citizens travel abroad to find safe jobs and send remittances back home, but some get trafficked.

The seed of this issue was planted in the 1960s. Former Philippines president Ferdinand Marcos weakened the country’s economy after misusing his power from 1966 to 1986. The economy’s fall pushed many citizens to seek jobs overseas.

But some migrants wound up getting sexually exploited after being lured overseas by a trafficker who falsely promised them a job. This problem exists today, but migration is booming in the Philippines.

Ten million Filipinos work abroad, according to global human rights agency International Labour Organisation. Over one million citizens migrate each year.

Child Rescue’s support

Destiny Rescue, funded by Child Rescue, first lept into the scene of sex trafficking in the Philippines after a super typhoon, Typhoon Haiyan, wreaked havoc across the nation in 2013.

With winds clocking at over 300 kilometres an hour, the storm killed 6000 citizens, displaced six million and made two million homeless. The event caused a wave of people to become vulnerable to the prey of human traffickers.

Fast-forwarding to today, Barnett, a rescue agent in the Philippines, says child sex trafficking remains a mammoth crisis in the country. But the abuse has been occurring more online than in red-light districts in the past seven years.

The Philippines first got the internet in early 1994 when its modest bandwidth of 64kdps fired off its first email saying, “we’re in”.

Since then, the internet got faster, cheaper – free in some public spaces – and spread like wildfire across the country, including villages in rural areas. Today, the nation has 74 million internet users. Smartphones are now popular too.

The internet soon became another place for child sex abuse to exist.

Early last year in the country, our rescue agents, alongside the nation’s law enforcement, rescued a two½-year-old boy from his father who sold pornographic images online of him molesting his son.

Because online child abuse is trending, Barnett says red-light districts now feature more cafes than bars, but predators still know where to hunt for child sex services. “It’s a lot more sinister,” he adds.

Physically, the landscape has changed … it’s not so in your face.”

This trend was catapulted by Covid-19’s rude awakening early last year. Since then, the government has enforced restrictions that have fully and partially closed sex establishments, sending pimps and exploited children back home.

Traffickers are now marketing and selling girls and women to customers online through chatrooms on social media platforms like Facebook and Viber. In some cases, girls are even selling themselves online without a trafficker’s control.

Child pimps

Online sex abuse might be soaring but traditional forms of exploitation continue.

Barnett says some girls, formerly exploited at bars in the city, are now selling themselves, friends and family on streets in their hometown in one of the country’s 81 provinces.

They don’t know what else to do, so they turn to the only thing they do know, which is trafficking or starting a trade of their own,” Barnett says.

Regardless of the pandemic closing bars, some girls have headed for provinces to sell themselves on the streets because they know they can make more money compared to a bar where their trafficker pockets half their income, he says.

“We haven’t worked in Manila in a good year or so. [For each case], we’ve travelled out three hours at least, north or south … and that’s per day,” Barnett says.

Barnett adds that child pimps are also becoming younger, saying he has trafficking cases involving girls who are 17, 16 and even 15 years old.

It’s the realisation of them making more money, the ease of prostituting friends or family.”

When our team helps find a child pimp, the Philippines’s criminal justice system typically tries to rehabilitate, not sentence them depending on the severity of their crimes. A government social worker is assigned to any child found in conflict with the law.

Adaption

Child sex trafficking is an ancient, forever-evolving crisis in the Philippines, and our team is ready to adapt alongside it to continue rescuing children trapped in sexual exploitation.

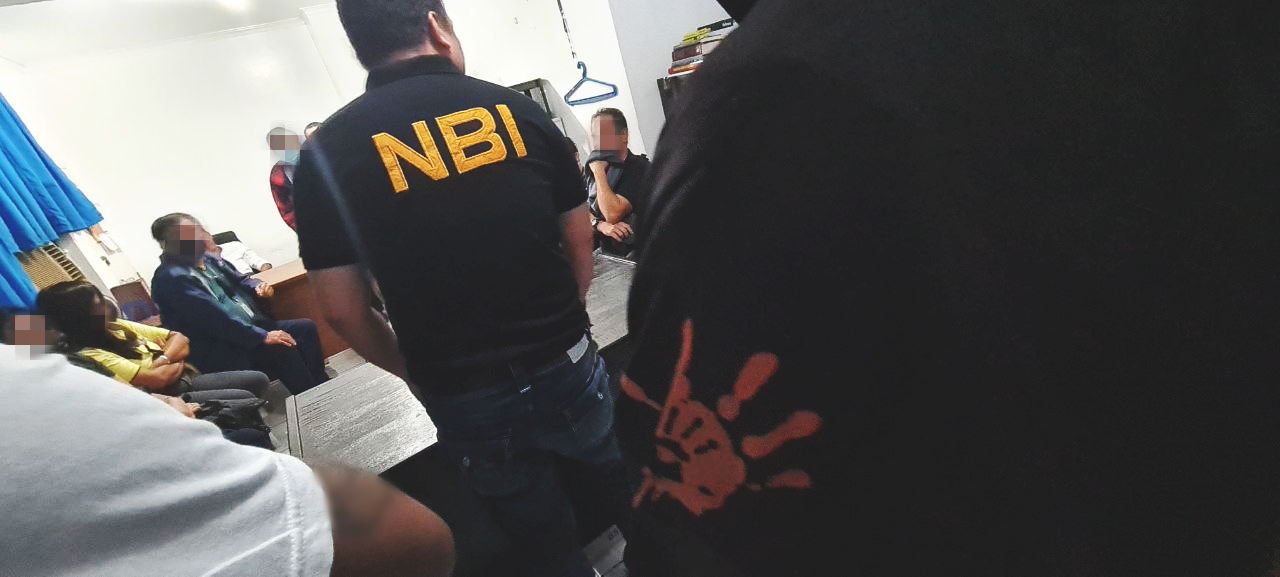

The National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) is the Philippine equivalent to New Zealand’s NZSIS and a close law enforcement partner of Destiny Rescue in the Philippines

Following the pandemic striking the world last year, there has been an “increase in activity” by pedophiles online, according to an article early this year by global child rights network ECPAT International.

Destiny Rescue, funded by Child Rescue, plans to launch an online task force of rescue agents, which allows abuse victims to call for support, to combat this new evolution in trafficking in the Philippines.

There is no choice but to expand. The need is massive,” Barnett says.

If you would like to fuel our dedication to eradicating this crisis, please consider donating today.

US & International

US & International Australia

Australia United Kingdom

United Kingdom