Rescue agents catch traffickers every year in Nepal. They’re literally at our team’s fingertips, but we often have to release them, like small fish.

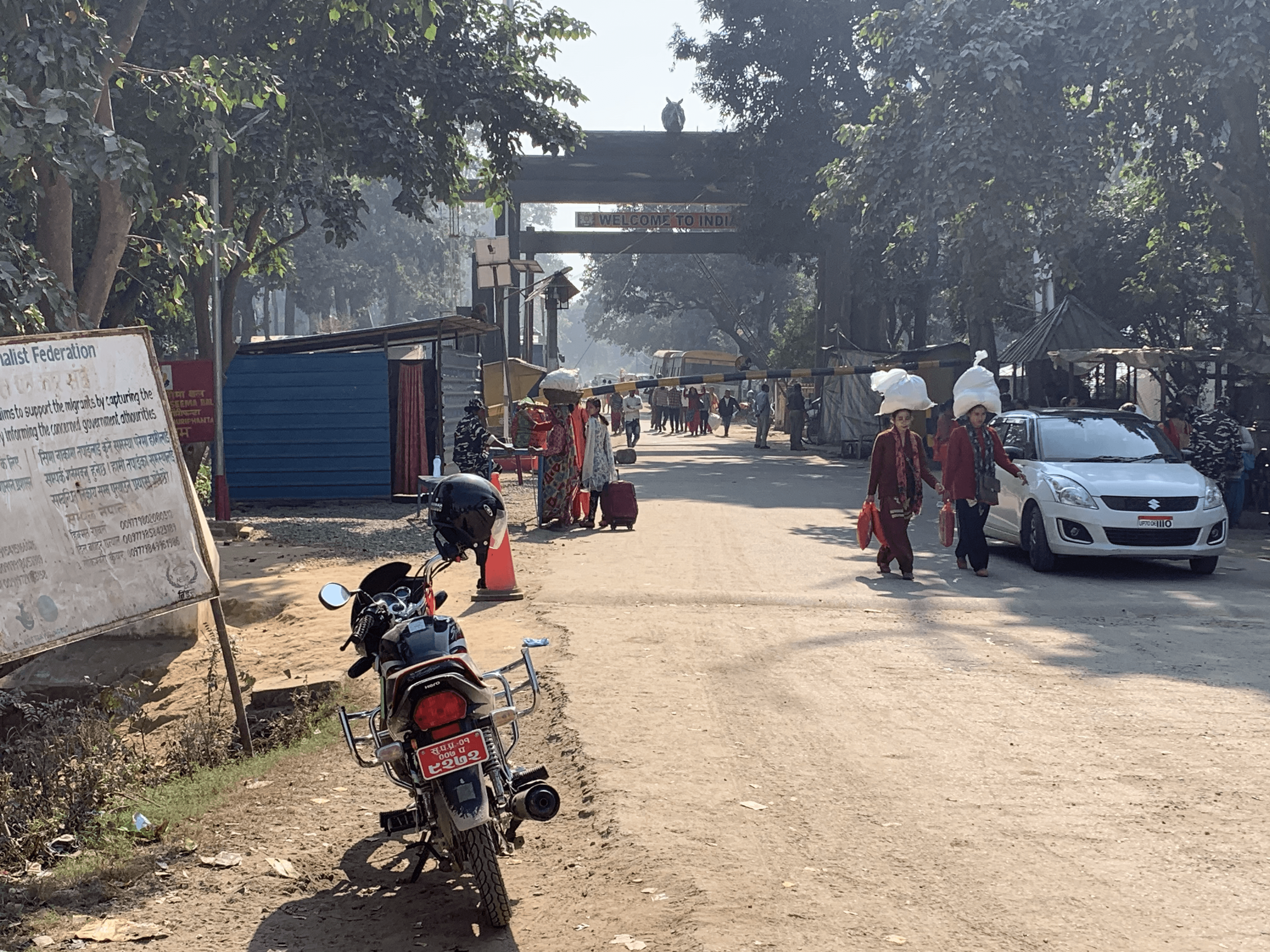

In Nepal, our border agents rescue hundreds of girls and women each year from crossing the border at 15 border stations circling the country. They’re stopped in their tracks because they’re on the cusp of being trafficked abroad.

The survivors are sometimes walking with their trafficker when brought to a halt. While our team can rescue the survivor and detain their trafficker, the ball is in the survivor’s court to press charges against him.

But it rarely happens.

About 97% of 560 survivors didn’t file a case against their trafficker this year. This is because they fear their community will learn about their incident and shame them for acting unorthodoxly, like trying to sneak off with a near-stranger abroad. Plus, survivors fear their trafficker.

Aarus, the project director in Nepal, says survivors can be bribed and threatened by their trafficker if they file a case against them.

[Survivors] would rather let the case go than go through this hassle,” he says.

But one survivor pushed against the tide last month.

The brave one

Sita, 19, is pressing charges against her trafficker after he nearly snuck her across the border and sold her in a neighbouring country.

Before meeting her trafficker, Sita had faced her fair share of hardships, like a broken family, childhood trauma, and losing her father to suicide.

Child Rescue funds 15 border stations around Nepal.

Sita lived under her sister’s roof when she became friends with Badal, 23, on Facebook. Badal – her disguised trafficker – told her he was from her motherland, ran a hotel and, eventually, asked her to get married abroad.

Trusting him, she slipped away to meet him at a hotel in Nepal. But in this hotel, she was sexually abused by him – a similar fate to 3% to 7% of survivors this year.

The hotel phenomenon

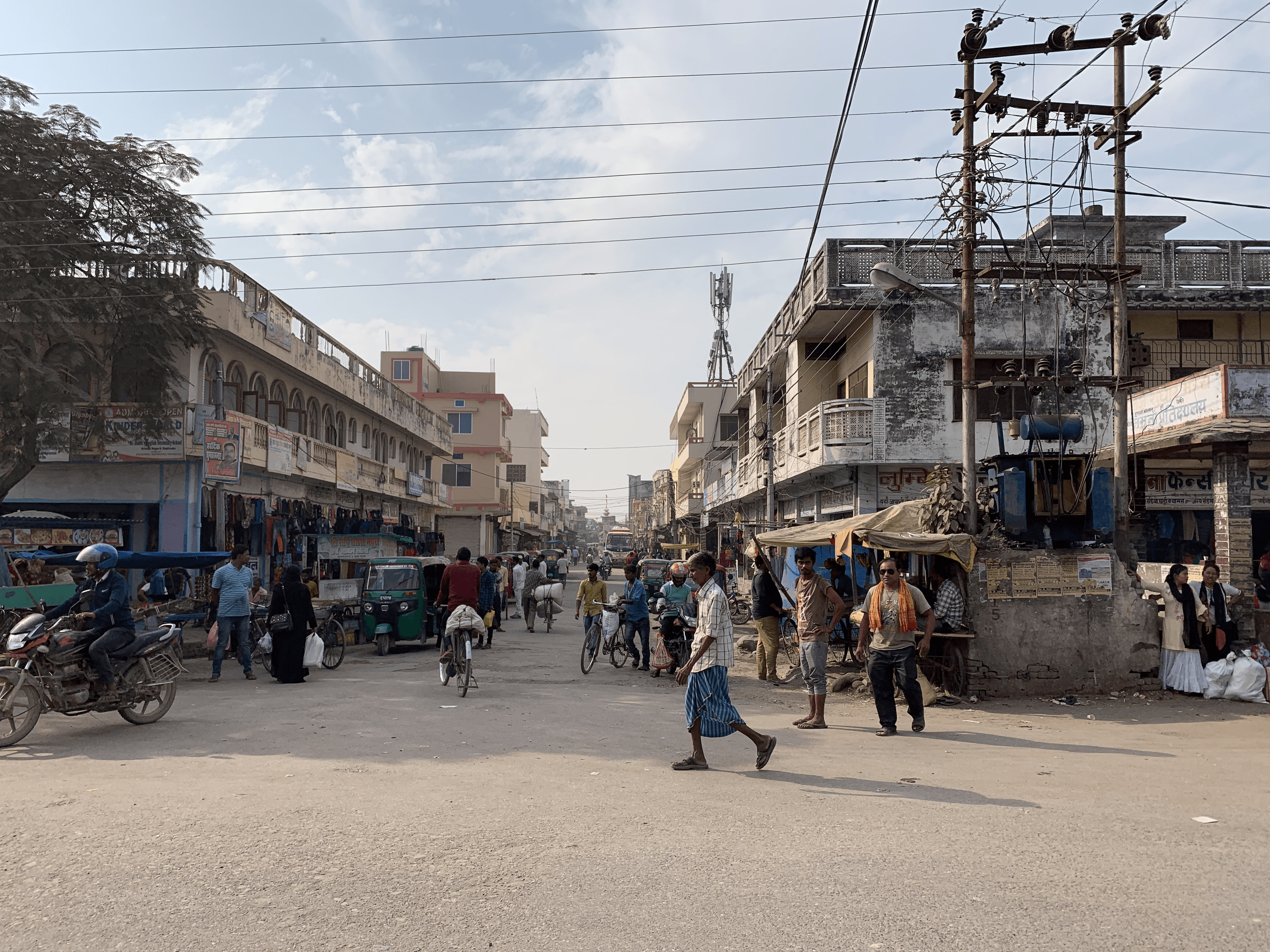

Traffickers, alongside their victim, might stay at a hotel in a town on the edge of Nepal before attempting to cross the border the next day.

Aarus, the project director in Nepal, says some traffickers have to stay at hotels because they can’t cross the border at night, as the border closes in the evening.

Here, a few traffickers take advantage of the stayover.

Nepal has about 1.3 million hotels.

Considering victims see their trafficker as a “saviour” for offering them a bright future abroad, traffickers can abuse their trust to have sex with them at hotels, Aarus says.

If the victim is a child or the encounter was forced, this ploy is a crime.

Unaware

Unlike other survivors, Sita nearly discovered the true, dark intentions of her trafficker. While at the hotel, Badal’s phone buzzed while he was in the bath. Sita answered and heard a man talk.

Did you get the girl? I have money ready for you,” the stranger said, according to Sita.

But she didn’t realise he was referring to her.

Given they’re desperate and the shine of their trafficker’s promise might be clouding their vision, victims of trafficking are often unwaveringly convinced they’re safe. Plus, the harder their home life is, the more likely they’re yearning for a bright future across the border.

Sita and Badal stayed at the hotel for three days. Afterward, Badal told her he would take her to a market but he headed for the border instead.

Badal attempted to cross the border with Sita when our border agents slammed the breaks on his plan. They stopped and questioned the pair before unmasking his true identity: a trafficker.

Sita was counselled and educated on human trafficking in Nepal, admitting that she had never previously considered the crisis a threat. Badal, on the other hand, was taken to a police station where he remains.

Sita filed a case against her trafficker, sparking heat from her trafficker’s family members. They have since tracked down and called her phone number, threatening her to drop the charges.

But Sita is fixed on serving justice to him.

Community shame

Sita falls under the three percent of survivors who have pressed charges against their traffickers in Nepal this year. This figure translates into 20 survivors, which is a “very concerning” number, Aarus says.

Aarus says there are two key reasons why survivors don’t file cases in Nepal: a drawn-out criminal justice process and community shame.

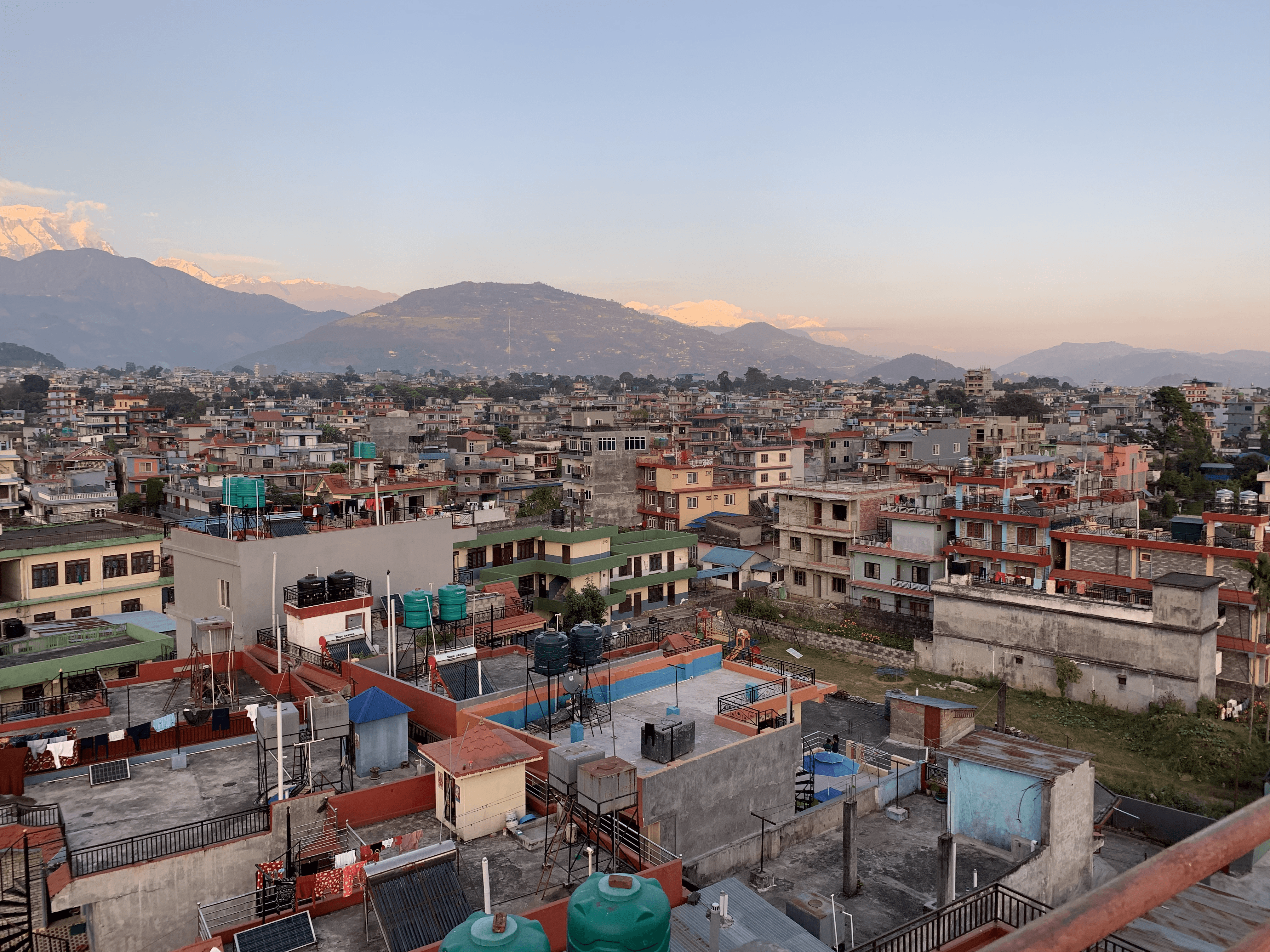

Nepal, a collectivist and conservative society, has an honour-shame culture. This principle is where people must follow social norms to uphold honour and avoid bringing shame to their family and community.

Most survivors, who are unmarried, refuse to file cases against their traffickers because they worry their community will shame them for disrespecting their culture’s conservative values while nearly being trafficked.

In her community’s eyes, a survivor might violate convention by lying to her family, escaping home, traveling alone with a man, and attempting to get married outside of her nation’s traditional route, an arranged marriage.

Survivors could face “humiliation, stigma and discrimination” from their community, Aarus says.

If they carry this shame on their shoulders, a survivor might also worry that her identity has been tainted, and no one will want to marry her within her community.

It makes it very hard for her to live,” Aarus says.

Survivors also don’t file cases because they don’t want to begin the journey of a “lengthy” and “hectic” criminal justice process, Aarus says.

If a survivor files a case, it can take a month before it lands in the hands of a district court, Aarus says. Court trials can take three to six months. Even if the trafficker is found guilty, the case could be appealed to a higher court.

On top of this, Aarus says survivors might be bribed or threatened by their trafficker during this process – reminiscent of Sita’s story.

We fight on

Asked for a remedy to survivors not filing cases, Aarus says it’s tricky. But they might do it if they were empowered and financially independent as they wouldn’t fear risking their identity given they don’t need a husband.

They could be the “bread earner herself so she can have her voice heard, and she gets all the confidence to fight for her right,” Aarus says.

US & International

US & International Australia

Australia United Kingdom

United Kingdom